As residents and visitors across the state begin to commemorate the 250th anniversary of the American Revolution, we cannot overlook the Camden Resolves, sometimes known as the “Little Declaration of Independence.” Signed on 5 November 1774, this document will be remembered at events in Camden during the first weekend in November.

So exactly what is this document? How did it come about and what did it mean? Before we can begin to understand the document, we must understand what was happening in Camden that brought about its creation.

By 1770, Camden was the only town located within the expansive Camden District, one of seven districts in the colony. The district was bounded by the Lynches River on the east and by the Congaree and Broad Rivers on the west. It extended from present-day Manning to the North Carolina state line and included what are now nine of the state’s counties: York, Chester, Fairfield, Richland, Clarendon, Sumter, Kershaw, Lancaster, and Lee. Also by this time, the colony was sharply divided between those who supported independence from Great Britain and those who remained loyal to the king. While support for independence was strong in South Carolina’s lowcountry, residents in this part of the colony were more focused on their “farms, orchards, herds, mills, and stores,” working hard to improve their circumstances from that of subsistence farmer to substantial planter (Partisans and Redcoats p 20).

By 1771 a courthouse and a jail had been constructed in Camden to serve the entire district. The first judges and sheriffs were British, appointed by British officials. By 1774, however, Judge William Henry Drayton of Charleston District had been named an assistant judge for the Northern Circuit of South Carolina, which included the Districts of Camden, Cheraw, and Georgetown.

On 5 November 1774, Judge Drayton came to Camden to preside over the grand jury as part of his routine tour of the judicial circuit. Over the previous decade Drayton had been more of a Loyalist than a Patriot, having served in the South Carolina Royal Assembly and on the Provincial Council in Charleston. In 1774, however, his allegiance shifted as British Judge William Henry Drayton (1742-1779) officials repeatedly appointed Englishmen to government posts that Drayton wanted for himself. This practice of the British appointing fellow Brits to American positions was problematic not just for Drayton but for many colonists, as the men who were being appointed had little knowledge or understanding of colonial affairs before arriving in South Carolina to fill a particular vacancy.

Finally, in 1774 Parliament’s passage of the Coercive Acts (known as the Intolerable Acts in the colonies) convinced Drayton that the “liberty and property of the American [were] at the pleasure of a despotic power” (South Carolina Encyclopedia p 274). In his charge to the grand jury at Camden, Drayton urged the jurors to defy British authority: “By as much as you prefer freedom to slavery, by so much ought you to prefer a generous death to servitude, and to hazard every thing to endeavor to maintain that rank which is so gloriously preeminent above all other Nations” (South Carolina Gazette, 12 Dec 1774). Drayton’s instructions to the grand jury were clear: “By the lawful obligations of your oath, I charge you to do your duty: to maintain the laws, the rights, the Constitution of your country, even at the hazard of your lives and fortunes.”

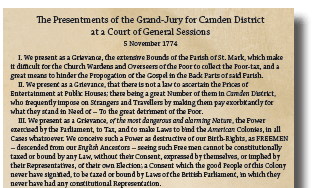

Judge Drayton’s charge led the twenty-two members of the grand jury to issue the presentments that we will be remembering in November. The document begins with three grievances: (1) that the extensive size of St. Mark’s Parish, in which Camden District was located, hindered the “propagation of the Gospel in the back parts of said Parish;” (2) that there was no law in place to standardize the “prices of Entertainment at public houses, there being a great number of them in Camden District;” and (3) “as a grievance of the most dangerous and alarming nature, the power exercised by the Parliament to Tax and to make Laws to bind the American Colonies in all cases whatsoever.” The signers went on to declare the following:

“We conceive such a Power is destructive of our Birth-Rights as FREEMEN — descended from English Ancestors — Seeing such Free men cannot be constitutionally taxed or bound by any Law without their Consent, expressed by themselves or implied by their Representatives of their own Election; a consent which the good People of this Colony have never signified . . . So now, that the Body of this District are legally assembled . . . we think it our indispensable Duty clearly to express the very imminent Danger to which [the people of this District] are exposed from the usurped Power of the British Parliament.”

Published in the South Carolina Gazette on 12 December 1774, Camden’s presentments were followed by similar documents from Cheraw, Ninety Six, Georgetown, and other districts in South Carolina. The Mecklenburg Declaration of Independence followed in North Carolina on 20 May 1775, and the Declaration of Independence written by Thomas Jefferson and signed by members of the Continental Congress came the following year. While all of these documents express similar sentiments about freedom, liberty, and tyranny, Camden’s was the first!